15 Nov Mass Timber: An Interview with BNKC Architects’ Jonathan King

We sat down with BNKC Architects Principal Jonathan King to discuss an area of increasing interest to business leaders in AEC industries: mass timber.

Tell me about BNKC’s transition into mass timber. How has the firm positioned itself to work in this sector?

The first major mass timber project we’ve been working on is 77 Wade Avenue for Next Property Group. The decision to go with mass timber was not a foregone conclusion, but rather the result of natural exploration with our clients. Many clients come to you with a set idea in their mind of what they want to do and how they want to get there. They have a formula, and they want you to execute the formula, end of the story. In this case, our clients were game to go on the journey with us to test out whether adopting a new system would be viable, both commercially and technically. So in the early stages, we ran two parallel design processes: a more traditional one exploring steel systems, and the other investigated a mass timber solution.

One of the things we did really early on was bring in a construction manager, a fabricator, and an installer to develop an integrated design process. Throughout this process, we were in constant dialogue with our team, which actually gave us and the clients a sense of comfort to explore different possible solutions, including a mass timber option.

The second thing we did, which turned the process on its head a bit, is engage with stakeholders at the outset, including all the authorities having jurisdiction. We wanted to involve them in the discussion early, which is not something you typically do. And so we brought the concept to the City, and through a back and forth — and essentially an alternate compliance methodology — we were able to get the approvals required to actually achieve a mass timber project at the schematic design phase. This gave our clients a real sense of security. We crossed a big hurdle at the beginning of the project and therefore reduced the risk of having a completely designed project get rejected by the City. The process not only allowed us to continuously innovate and refine our design throughout schematic, but also use early costing to modify our approach.

We know that from an international perspective, Canada’s behind the ball when it comes to mass timber construction, especially in light of the fact that we’re such a timber-rich country. From what you’re describing, it sounds like these new projects are pushing policy from the ground up. Is that a fair assessment of how building codes are starting to change?

It’s a great observation. One of the things we recognized very early on is not only did we need to have the right fabricators and installers involved, we also needed to have the right consultant team, which included engineers at Blackwell and our code consultant, Vortex. 77 Wade is a code-breaking building. Code was actually a very big part of how we engaged with the City, met their requirements, and ultimately found a solution that allowed us to build a structure in which almost 80% of the mass timber is exposed. This is unique in that most buildings above six storeys have been executed by covering up the mass timber with drywall. One of our client’s mandates was to execute a mass timber structure in which everyone could benefit from the biophilic qualities associated with living, working, and playing inside a wood building, so one of the main tasks was to make sure we exposed as much timber as we possibly could.

Interior Rendering. 77 Wade Avenue. Courtesy BNKC Architects & Cicada Design Inc.

Aside from building codes, what are some of the biggest barriers to building with mass timber in Ontario?

One of the biggest hurdles remains the supply chain. We don’t have a robust supply chain in Canada at the moment; however, there are ongoing efforts to grow that capacity. Element5, for example, is building a facility that is slated to open in December or January of this year, and there are others coming online. With the introduction of these fabrication facilities, we’re going to have a more readily available supply, which in turn should reduce costs, hopefully by as much as 10-15%. Up until now, there’s a perceived premium associated with the use of mass timber systems in projects, which is one of the primary reasons we don’t see more projects employing timber as a solution.

You said “perceived premium.” Can you elaborate on cost versus the value proposition of mass timber?

I say “perceived” even though we haven’t really seen [premiums] on our project. That’s because we’ve tried to ensure that we are sensitive to market fluctuations and able to change out certain systems if need be. For example, on 77 Wade, we started out with the intention of using NLT (nail-laminated timber), but actually ended up going with GLT (glue-laminated Timber), which was a direct result of market forces. Two out of three fabrication facilities that produced NLT in Ontario closed down last year and it became unviable for us to consider NLT with only one potential supplier. So GLT presented an opportunity to mitigate supply risk and address that scarcity. We’ve modified our design and are about to resubmit it for building permits.

Managing costs is part of a holistic conversation, not one just focused on construction costs. If you want to do it right, you need to address things from the perspective of a whole project, which also includes the marketing and the lease-up of the building. What we’ve found is that developers are able to recognize the value-add that comes with using wood. Any additional cost associated with mass timber is actually absorbed into the overall financial scheme and not seen as a hurdle. At the end of the day, if you prioritize elements like biophilia and sustainability, then frankly I think you come out ahead.

Sectional Rendering. 77 Wade Avenue. Courtesy BNKC Architects & Cicada Design Inc.

On the subject of biophilia, in your opinion — buzzy wellness trend or here to stay?

I’m not a scientist or a social engineer, but I’ve been designing with mass timber for many years and you can see the way people experience these spaces. There’s a direct correlation between feelings of wellness and wood environments. That goes hand in hand with access to natural light and air quality. And COVID only heightens the desire to ensure that work environments are healthy and clean quality spaces. So no, I don’t think it’s a “here today, gone tomorrow” type of trend. It’s something we will need to pay attention to and continually champion.

What are some of the most common misconceptions you encounter when it comes to mass timber, aside from the idea that it costs more? Are there any unexpected benefits that accrue when you adopt this building system?

I think the insurance industry needs to understand what mass timber is, that it’s distinct from wood and not a fire hazard. This remains a big misconception and a lot of education still needs to take place. I also think we haven’t fully understood or tapped into the inherent benefits of using this material and the impact it can have on a community.

There’s actually a pent-up demand for wood structures. Once our supply chain and fabrication systems are figured out, I think we’ll find ourselves in a far stronger, more enviable position than many of the European countries. They’ve got 40-50 years on us when it comes to mass timber experience, but we have more resources at our disposal. We can certainly benefit from bringing some of the learnings from Europe to Canada and making timber a truly Canadian solution.

Even within mass timber, there are many more solutions that have yet to be explored. One of the things I keep pushing up against is the institutional demand for mass timber. Right now, every university, every college wants a mass timber building. We’re actually not going to see the real supply chain benefits until mass timber also finds its way into commercial and residential markets. If we really want to move the dial on sustainability, minimize premiums, and have mass timber be a truly viable alternative, we need to see a greater critical mass of projects using that system.

Are there things we can do with mass timber today that we couldn’t accomplish even five or 10 years ago?

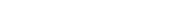

I’m not a purist, which I think is one of the reasons we’ve found a good solution for 77 Wade. When contemplating mass timber, you can’t think about it from the perspective that everything has to be wood. The systems that we’re exploring and proposing are hybrid in nature. We’ve taken systems seen in other typologies, including retail/commercial offices, which have used a combination of DELTABEAM with precast concrete slabs, and replaced them with NLT & GLT, resulting in a building that is 30-50% wood. By mixing and matching different structural systems, we’ve solved both the problem of span and beam shadowing.

We went back to first principles and considered what systems are out there and how we could mix and match or hybridize them to create better solutions. What we’ve done is to employ the properties of wood, steel, and concrete where they need to be, and in doing so we’ve tackled the key structural factors that needed to be addressed. The result, in the case of 77 Wade, is polished concrete floors, exposed wood ceilings, and open floor plates at significantly lower costs. We’ve also maximized floor-to-floor heights and increased structural bay spans, so occupants can benefit from 12- or 13-foot ceilings. By effectively creating flat slabs, we been able to avoid the need for raised floor solutions, allowing for flexibility of floorplates, increased overall floor-to-floor height, reduced energy costs, and reduced construction costs across the project. It’s an integrative approach.

Axo Diagram. 77 Wade Avenue. Courtesy BNKC Architects.

Does BNKC embrace a particular philosophy or enlist specific methodologies when it comes to approaching mass timber design?

This hybridizing approach — employing some wood on every project rather than just doing one project that’s a home run — is one I continue to embrace. I’ve always said that I’d rather have 30 hybrid buildings than one purely mass timber building.

The other thing I’d highlight is collaboration. We pride ourselves on our ability to collaborate, not just with consultants and clients, but with other architects. For example, we’ve teamed up with firms from the UK, like WilkinsonEyre, to pursue particular Canadian projects because we’ve recognized that they have something that we don’t, and vice versa. It’s always a team effort. Collaboration leads to capacity building — it’s how you learn.

We believe in the cross-pollination of ideas and typologies, and tackling more complex projects from a position of curiosity. That’s what brings us to potentially different solutions; we don’t default to the status quo. And frankly that’s what brought us to working with mass timber.

From a sustainability perspective, it’s obviously great to bring biophilic qualities to a space. But as a firm we also very much respect the economics of every project. If it’s not viable economically, then we’re not going to push mass timber for the sake of it.

Are there specific steps your firm has taken to ensure your team is equipped with the right skill set and expertise to work with mass timber?

Like every architect and designer, we pore over the latest articles and data, and attend all the seminars and sessions in the area. I also attend and speak at various conferences, such as the International Mass Timber Conference in Portland.

I make a point of visiting sites and speaking with colleagues to see where they’ve experienced successes and challenges. In fact, just recently I was at a new 5-story mass timber residential building site down on Queen Street East. And that’s part of the education — going out there and seeing how others are executing.

We also frequently visit fabrication facilities. I recently went out B.C. to tour StructureCraft’s facility to gain a better understanding of the systems they’re developing as well as the opportunities and limitations of various timber products. That’s the fundamental difference with mass timber as a material: it’s not enough to just design with timber, you actually need a deep understanding of the fabrication process. You’d never go out to a steel fabrication or concrete mixing facility, but mass timber is different. Projects are built in the factory and then brought to site; knowing the ins and outs of the fabrication process is fundamental to the design.

What opportunities have we yet to take advantage of when it comes to mass timber?

The building construction industry is notoriously behind in their systems. Look at other industries out there. The car industry is a great example. Car manufacturers have figured out how to capitalize and innovate their production to deliver higher-quality, affordable technology to the public.

In that sense, mass timber is a kind of Holy Grail for the construction industry. The reintroduction of wood into our toolbox has, for the first time in years, given us the opportunity to truly innovate the kind of work that historically has needed to happen on-site. It’s allowed us to better respond to variables like weather, labour, material shortage, and transportation by moving things into a controlled environment: the factory. Even if you shift only 15-30% of a project that is traditionally developed on-site offsite, you gain further control of the construction process, lower costs, and reduce the risk profile significantly.