15 Nov Mass Timber: An Interview with MJMA’s Ted Watson

We sat down with MJMA Partner Ted Watson to discuss an area of increasing interest to business leaders in AEC industries: mass timber.

Are there any particular steps that MJMA has taken internally to ensure that your team stays up-to-date on the latest developments in mass timber? How can you help your team members, from a capacity-building perspective, develop the right skills?

One of the things we did about two years ago was bring on our Director of Sustainability, John Peterson. He’s there to ensure that we’re pushing hard from an innovation and sustainability perspective on all of our projects, not just the exemplar ones. Whether it’s a Net Zero project that requires specific expertise or a more typical arena, for example, which uses a ton of energy, he advises on how to make it as efficient as possible.

We also advanced Leland Dadson to Mass Timber Specialist, as he has significant experience with CLT and technical detailing. He participates in all of our wood projects and is responsible for teaching people in the office, bringing in resources, meeting with people in the industry. Myself and others do that as well, but Leland is the main point person on timber. Developing this role was a deliberate strategy for concentrating information and knowledge and disseminating it effectively.

These roles became a priority because we really wanted people who would enlighten us and hold our feet to the fire when it comes to sustainability. It was a philosophical decision, a commitment to a core value at the highest level. Our firm has designed passively and sustainably for decades. It’s always been a part of our ethos; we’ve even developed a fully documented in-house Sustainability Charter. But when you start to get into Net Zero energy buildings and LEED Platinum, it becomes even more complicated. The energy modeling required for these projects is very complex, and if you really want to innovate and do these things well, you need to have people who are focused on these aspects and consolidate that knowledge in-house.

Interior Rendering. University of Toronto Academic Wood Tower. Courtesy MJMA & Patkau Architects.

What are some of the challenges you’ve encountered in persuading clients to accept mass timber as a viable structural material? What are some of the most common misconceptions that they have?

The most common misconception is that the final product is going to cost more. And yes, it’s probably going to be more expensive, but you also have to consider that you’re not going to put in a lot of finishes that you would have otherwise. A wood structure is very expressive in its own right. It’s also biophilic and offers so many added benefits.

When people hear mass timber they also think “well that’s gonna be a fire trap.” In reality, the best analogy is to think about it in terms of kindling versus logs. Kindling has a number of re-radiating surfaces that catch and perpetuate fire, whereas mass timber is more like a log — if you try and light a log with a match, it doesn’t ignite. There are actually greater fire protection strategies put in place. The other big misconception is thinking the structure will fail if it’s burning, but it doesn’t. It actually preserves itself because of something called a char layer. Structurally, the wood at the centre of that char layer actually performs perfectly well during a fire. So these are safe buildings. Most of the tall timber buildings we have designed have a two-hour fire rating, so they can burn for two hours and the structure will still remain in place.

Can you elaborate on cost versus the value proposition of mass timber? How do you have that conversation with clients?

Generally speaking, the structure of a building is worth maybe 20% of its construction value. It’s roughly a 5-15% premium over the standard cost to go to a wood structure. It’s a few percentage points on your construction budget, which is not a small thing when those costs potentially interfere with your ability to deliver your client’s program. But then you ask the question: “Where can we economize and save money to make a timber version of this project possible?”

For example, right now we’re working on a fitness pavilion as part of Princeton University’s student center. The goal is to create a highly sustainable and transparent building, an environment that breaks down the barriers to participation and encourages students to come in, relieve stress, and develop healthy lifestyles and socialization patterns that will last a lifetime. Our approach was, “Let’s have a wood structure. We won’t have any ceilings. We won’t have a lot of things that you would normally have otherwise, but we’ll create a welcoming environment that you not only experience on the inside, but also from the outside.” This was our conversation with the client. The value of the wood structure is that you put some lights on it at night, and it generates a warm feeling. Everyone enjoys that experience. How do you put a dollar value on that? It’s a clear intangible, but it also delivers a level of functional performance that you set out to achieve.

There’s been lots of discussion about the biophilic advantages of wood in the last few years. In your opinion — buzzy wellness trend or here to stay?

That’s a good question, fad or fixture. Biophilia is a term that’s been used pretty liberally to talk about health and wellness in buildings, but I think it’s always been here, so yes, I think it’s here to stay. People are starting to recognize — and the research backs this up — that wood structures, daylight, and biodiversity inside and outside of buildings all have a huge impact on people’s sense of well-being as well as staff satisfaction and retention. A great argument for spending more money on design that uses wood, particularly in work environments, is that if you look at the cost of an office building, the capital cost is logarithmically dwarfed when compared with a 30- to 50-year life cycle that incorporates staff considerations like sick days and retention. There’s a strong financial argument for investing in great biophilic design.

Are there any unexpected advantages or added values to building with timber that clients aren’t aware of at the outset?

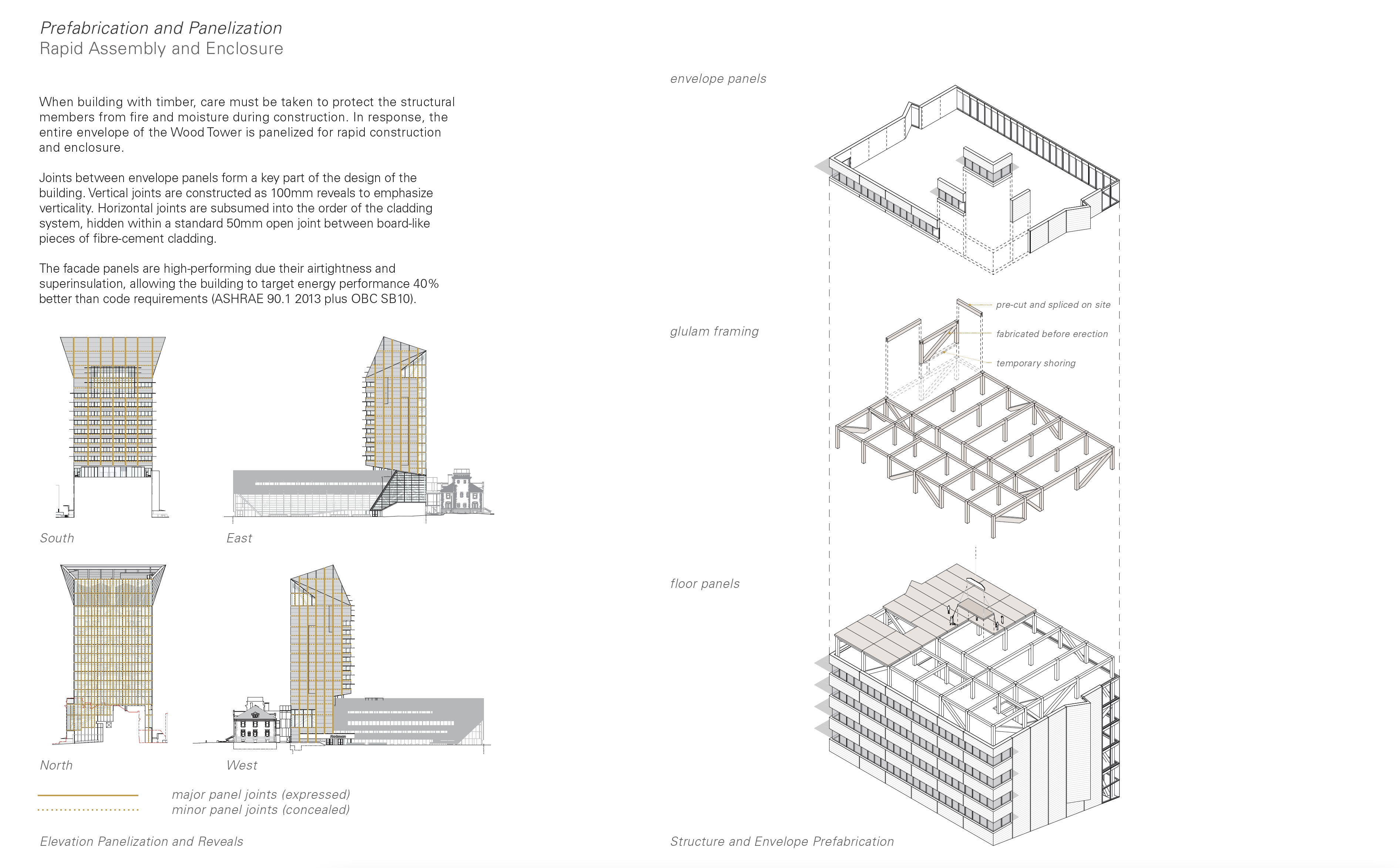

Yes. Here’s a very pragmatic example: a wood structure can go up extremely quickly and extremely quietly, much like putting together an Ikea bookshelf. These things can be built in record time, with less transport, less noise, and less dust. For example, the University of Toronto Academic Wood Tower we’re working on in collaboration with Patkau Architects is going up right next to a student residence and surrounded by occupied academic buildings. Our clients recognize how quiet the construction site can be and have expressed how valuable that it is to them. Their appreciation of this has been very insightful for us.

The other big advantage that I think is a great opportunity for clients is the mass timber ‘story’ and how the use of wood becomes a progressive expression of your brand. At U of T, the main tenants will be the Rotman School of Executive Business and the Munk School of Global Affairs and Public Policy. If you’re walking along Bloor Street and you look south from there, you will see highly recognizable buildings like the Bata Shoe Museum, Varsity Stadium, and the Royal Conservatory of Music, and then this mass timber tower, and you wonder, “Wow, who’s in that building?” The project tells a story about innovation and sustainability, and is also advancing the use of timber in a new sector. The Arbour project at George Brown College is another pioneering development in this regard.

Competition Entry. George Brown College: The Arbour. Courtesy MJMA & Patkau Architects.

Does MJMA enlist any specific methodologies when it comes to approaching mass timber design?

Wood has some limitations in terms of its typology. We know it’s great for offices and residences, but can it be used as successfully in labs and academic buildings? Working in collaboration with Blackwell, our structural engineering partners on the George Brown Arbour competition, we developed a hybrid floor structure assembly — bubble-laminated timber (BLT) — comprising concrete, wood, and plastic balls that helped create void forms in the final laminated structure. This hybrid solution resulted in wood that could span much greater distances and had better vibrational qualities due to the incorporation of concrete. It also became an analogy for how we approached the entire project as an optimal hybrid system. Our thinking, in part, was to resist being dogmatic about creating an entirely wood structure, which is maybe why we didn’t win! But at the end of the day, we think that if we can introduce more timber into projects, even if it’s incremental, the use of wood becomes more commonplace. And that’s a big win for its advancement and the environment.

From an international perspective, Canada is behind the ball when it comes to mass timber, especially in light of the fact that we’re such a timber-rich country. What are some of the biggest barriers to building with mass timber in Ontario and Canada?

Although the current building codes still make it challenging to use mass timber to a great extent, that’s shifting. Changes are starting to happen in the National Building Code as well as the International Building Code, and we anticipate that we will be allowed to use wood construction to build higher and higher structures.

One of the other big challenges is getting good cost estimates. For example, MJMA is currently using mass timber in several projects with wood roofs. The industry is generally more familiar with that use of timber, so it’s easier to get quotes from contractors and fabricators. But when you start designing a mass timber tower that’s 80 meters high, one of the biggest challenges is estimating time and budget. You know you’re going to get certain wins on the project — the on-site construction time will be shorter, for example — but how do you know how short that period will be if no one’s done it before, and what are the savings? The only way we can get better at estimating budgets and schedules [with mass timber] is by constructing more buildings. The more we see developed, the more knowledge we’ll accrue.

What we’ve been recommending and trying to implement is an Integrated Design Process (IDP) so that construction management is baked-in early on. Rather than design the building and then tender it out to five general contractors, we’re trying to institute an early construction management process in which the contractor is working with us from the outset to help set the price. Within that framework, we are able to do a design assist and bring in specialty contractors who work exclusively with mass timber so that we’re designing to meet specific manufacturing requirements. That puts us in a much better position with respect to securing price and supply certainty. The challenge is that it’s a more robust process and requires a larger commitment from the client and all the consultants to make it work.

What are some of the opportunities that we have yet to take advantage of when it comes to mass timber design and construction?

I think the future of mass timber and construction is still prefabrication. Perhaps the problem is people have been saying this for so long that no one believes it anymore, but we’re starting to get there. We’re designing everything in Revit now, so literally we’re building in 3D models that can be handed over to a contractor for prefabrication. Increasingly things are built in a warehouse and then plugged in on-site. And students are being trained in parametric design. We’re making progress, but I think the construction industry remains very ripe for a total disruption. And I think we’re trying to figure out who’s going to be the first to do it.

The number one way to get to a Net Zero and carbon neutral future is to have more efficient energy within our buildings. We also have to have great building envelopes, more carbon-encapsulated wood, and higher quality standards. Prefabrication and Passive House design approaches help deliver on that promise by making great envelopes to higher quality standards in a factory and then delivering them to site. As part of the design solution for our Wood Tower at U of T, for example, we’re looking at a prefabricated envelope that will be produced off-site and then ultimately “pasted” on. It’s one of the challenges, but it’s also one of the things that’s going to make mass timber really innovative as it becomes more commonplace.

Prefabrication and Panelization: Rapid Assembly and Enclosure. University of Toronto Academic Wood Building. Courtesy MJMA & Patkau Architects.

Are there things we can do with mass timber today that we couldn’t accomplish even five or 10 years ago? How quickly is it advancing as an industry?

We’ve been making technological advances — the advent of cross-laminated timber (CLT) over the last 20-30 years has really changed things — but I think the key is making mass timber construction common practice. And that comes back to promoting its use and amending the building codes. As architects, it’s our job to present alternative building solutions to the City of Toronto that push the Ontario Building Code and work with the Fire Department to troubleshoot and test things. I think that’s one of the things we’re seeing advance — building codes are recognizing that timber is going to be an important solution in the future, so the codes are being adjusted to allow for that to happen. In the meantime, folks like us and specialists like our consultants are writing huge, encyclopedic reports that include a lot of testing, data, and research to help the cause.